Early in my career, I was galvanized by a disease that ravaged my country and many others around the world: malaria. My personal experiences with malaria in the field as a young public health officer twenty-seven years ago had a profound effect on my trajectory. Soon after joining the Ministry of Health in Ethiopia, I was called upon as part of team to respond to a malaria outbreak. My team was dispatched to a village in South-Western Ethiopia, where I not only observed the malaria epidemic’s shocking effects on adults and children, but also experienced it first-hand. I contracted malaria while working in the field. That was the impetus for me to pursue a doctorate in community health. As a young academic, I investigated the patterns of malaria’s spread and the potential measures we could employ to control it.

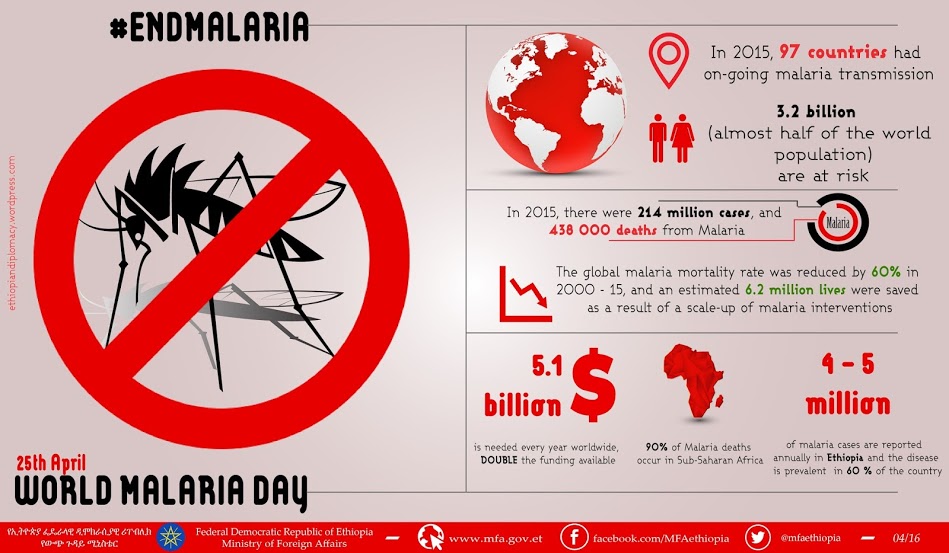

Last year, nearly 214 million cases of malaria occurred globally, leading to 438,000 deaths. Ninety percent of malaria deaths occurred in Sub-Saharan Africa — and the majority in children under five. Nearly half of the world’s population — roughly 3.2 billion people — are currently at risk for the disease.

The monetary impacts of malaria from the household to the global level are significant. Malaria tends to strike during harvest season, rendering families too sick and too weak to perform the work necessary to earn a living. Malaria-stricken families spend an average of over a quarter of their income on malaria treatment. In Africa alone, the economic impact of malaria is estimated to be US$12 billion every year.

During my period as Minister of Health of Ethiopia from 2005 to 2012, we designed a comprehensive malaria control strategy with ambitious targets, and made a robust government commitment to the effort. The tenets of our comprehensive approach included vector control, early diagnosis, prompt treatment and surveillance, and rapid management of malaria epidemics when and where they occurred. In addition, we undertook the monumental task of distributing 22 million long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets over a two-year period. In doing so, we protected 50 million people at risk, increased bed net coverage from 6 to nearly 70 percent, and reduced malaria deaths by more than 75 percent.

We broke the cycle of Ethiopia’s epidemics — which previously occurred every 5-6 years and sometimes as often as every 24 months — and achieved the Millennium Development Goal for malaria. Ethiopia transitioned from the objective of preventing and controlling malaria to the realistic goal of malaria elimination. The knowledge we gained about our successful approach to malaria within Ethiopia was instrumental in my later chair positions on The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Malaria and Tuberculosis and the Roll Back Malaria Partnership.

So much has changed since I first joined the struggle against malaria. In the past 15 years alone, malaria mortality has fallen by 60 percent globally — resulting in an estimated 6.2 million averted deaths. We now have a chance to eliminate the disease and render it powerless, much like polio and smallpox. But on this World Malaria Day, we are reminded that our extraordinary advances are fragile and that the fight must continue. Malaria still kills more than 400,000 people annually and drains hundreds of millions of dollars from developing country economies. There are 100 countries where malaria is endemic, and many more where success is tenuous.

Defeating malaria is absolutely critical to ending poverty, improving the health of millions and enabling future generations to reach their full potential. What can we do to reach this goal?

We must continue to expand partnerships across borders to secure the financial and technical resources we need to make and sustain progress. Efforts should focus on disease prevention and control, including early detection, diagnosis and treatment. We must prioritize vector control by distributing insecticide treated bed nets and spraying to control larvae and the adult mosquito population. Community-based programs remain essential to ensuring that communities are empowered to be actively engaged in the prevention and control of malaria. Responsive health systems with universal primary healthcare at the centre will enable more effective preventative measures against malaria. And finally, investments in the development of next-generation drugs, diagnostics and vaccines will help us to accelerate our gains and mitigate the rising threat of insecticide resistance.

Without adequate funding and a coordinated global approach, malaria resurgence could claim millions of additional lives. On this World Malaria Day, let us pause to acknowledge and take pride in our tremendous progress against malaria and renew our firm commitment to end this scourge for good.

This article was written by H.E. Dr. Tedros Adhanom, the Foreign Minister of Ethiopia and originally posted on the Huffington Post on the 25th of April 2016, on the occasion of World Malaria Day.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is the Foreign Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. You can follow Dr. Tedros via Twitter.

Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus is the Foreign Minister of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. You can follow Dr. Tedros via Twitter.