The UN Monitoring Group concerned at Eritrean arms embargo violations…

The UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea released its latest annual report on Eritrea on Friday last week (November 4). The report covered several different areas of concern: Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates establishment of a military presence in Eritrea, Eritrea’s continued support for armed groups involved in regional destabilization, the question of Djibouti prisoners of war, the possible use of mining revenue to break the arms embargo and a mission to Italy in search of spare parts for helicopters, and the repeated refusal of the Eritrean government to engage with the Monitoring Group.

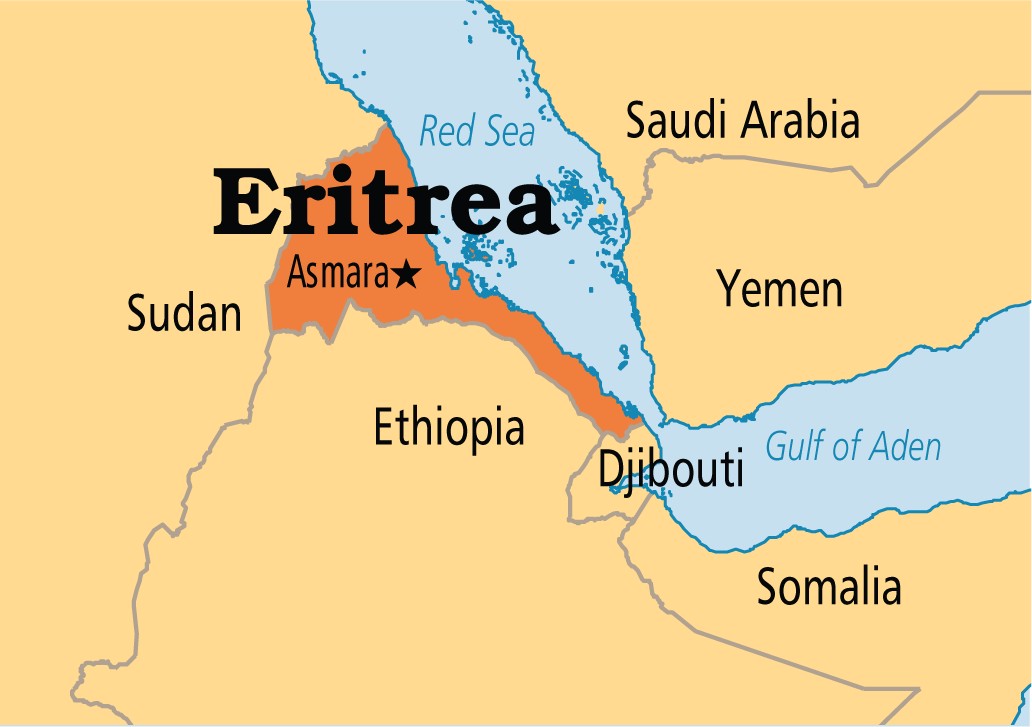

The report noted that Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates had established a military presence in Eritrea as part of the Saudi-led coalition against Houthis in Yemen. It said the use of Eritrea’s land, water and airspace by other countries to conduct military operations in a third state was not, in itself, a sanctions’ violation, but it noted that “compensation diverted directly or indirectly towards activities that threatened peace and security in the region, or for the benefit of the Eritrean military, would constitute a violation.” It also said it had collected evidence that the construction of a new permanent military air base and a permanent sea base at Assab provided “external support for infrastructure development that could benefit the Eritrean military.” The Monitoring Group also said it had documented the presence in Eritrea “whether for training or transit, of armed personnel and related military and naval equipment of various Member States other than Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.” Indeed, Eritrea’s Foreign Minister told Reuters earlier this year that the United Arab Emirates now used Eritrean “logistical facilities”; the UAE had also trained 4,000 Yemeni fighters at Assab. The Monitoring Group said it was clear that foreign support for the construction of permanent military installations in Eritrea amounted to the provision of technical assistance, training, financial and other assistance to Eritrean military activities. The current terms of the U.N. arms embargo on Eritrea do not allow for such activities. These are banned under the arms embargo.

With regard to support for armed groups, the report noted that for the third year running it had found “no firm evidence of Eritrean support for the Somali Islamist group Harakat al-Shabaab al‑Mujaahidiin”. The Eritrean authorities seized upon this to claim that this meant the Monitoring Group had found no evidence of sanctions breaking and that therefore that what it claimed were these “unjust” sanctions should be lifted. In fact, of course, support for Al-Shabaab was only one of the reasons for the impositions of sanctions by the UN Security Council at the request of the African Union.

In its latest report the Monitoring Group, as usual, defined its mandate. One element of this is that it should monitor the implementation of the Council’s demand for all Member States, “in particular Eritrea, to cease arming, training and equipping armed groups and their members, including al-Shabaab, that aim to destabilize the region or incite violence and civil strife in Djibouti.” While the Monitoring Group said it found no “firm” evidence of support for Al-Shabaab, it certainly found considerable evidence of arming, training and support for a number of other groups which have publicly committed themselves to regional destabilization as well as indications of Eritrea’s support for the armed Djibouti opposition, the Front pour la Restauration de l’Unité et de la Démocratie (FRUD). This carried out low-level attacks in northern Djibouti throughout the current mandate and continued to undermine the normalization of relations between Djibouti and Eritrea and obstruct the implementation of Security Council resolution 1862 (2009).

In fact, this latest report says firmly that the Monitoring Group “continued to find consistent evidence of Eritrean support for armed groups operating in both Ethiopia and Djibouti.” It adds: “It is clear that Eritrea continues to harbor anti-Ethiopian armed groups, including the newly remodeled Patriotic Ginbot 7, and provides at least some logistical support to them.” It said former fighters, including the former Chairman of the Tigray People’s Democratic Movement, Mola Asgedom, provide evidence that the Eritrean authorities were providing weapons and training to these groups but because the Eritrean Government continued to refuse to allow the Monitoring Group access to Eritrea, it was unable to determine how far the Peoples’ Alliance for Freedom and Democracy, incorporating such anti-Ethiopian movements as the Ogaden National Liberation Front and the Oromo Liberation Front, might pose a threat to Ethiopia. However, the Group appeared to have to have no doubt that the Eritrean authorities were continuing to provide substantial support to armed groups aiming to destabilize the region in defiance of Security Council resolutions.

In the context of Djibouti, the Monitoring Group also raised the disappearance of 11 Djibouti soldiers whose whereabouts have been unknown since 2008. During Eritrea’s attack on Djibouti in 2008, 30 Djiboutian soldiers were killed, 39 injured and 49 handicapped, with 19 reported missing in action, presumed to have been taken prisoner. The Government of Eritrea refused to acknowledge that it held any Djiboutian troops. Nor, incidentally, did it ever enquire about the 17 Eritrean soldiers held by Djibouti, and it still has not done so. Two of the Djibouti prisoners escaped from Eritrea in 2011, a further four of the missing combatants, held incommunicado as prisoners of war by Eritrea since 2008, were released in March 2016 after further intervention by the Government of Qatar, the mediator in the dispute. In September 2016, the Permanent Representative of Eritrea to the United Nations informed the Monitoring Group that one prisoner had died in detention and there were no more Djiboutian prisoners of war in Eritrean custody.

While the Monitoring Group welcomed this information, it also pointed out that this left 12 other Djiboutian prisoners unaccounted for. It stressed that “if this is indeed the case, it is vital that Eritrea confirm the circumstances of the death of the other combatants, whether on the field of battle or in custody, and, if the latter, the cause of death and place of burial.” It pointed out this was a requirement of the Security Council, and also a requirement of international treaty and customary law by which Eritrea was also bound.

Another area the Monitoring Group is mandated to investigate is violations of the arms embargo and to what extent revenue from mining, for example, may be contributing to help violate Security Council resolutions 2023 (2011) or 1907 (2009). Owing to the government’s continuing lack of transparency, the Monitoring Group said it had made no further progress in determining this. Equally, it noted the persistent failure of the Canadian mining company, Nevsun, to help determine whether any revenue from its Bisha mine might be used in this way. The question of diversion of unaccountable funds remained of concern. The Monitoring Group said it would, therefore, continue to watch British Columbia court case over the use of forced labor at Nevsun’s Bisha Mine. It noted UN Security Council resolution 2023 (2011) imposed an obligation on Member States to take measures to prevent funds from the Eritrean mining sector being used in this way. Canada, the US and the EU have all been developing mandatory measures that are due to become operational over the next two years. The Monitoring Group says this will increase transparency over government revenue; but it will not, of course, address the issue of government expenditures.

The Monitoring Group also documented concerns over the visit of a group of Eritrean air force officers, headed by Major General Teklai Habteselassie, Eritrea’s air force commander, to Italy this year. The delegation included two helicopter pilots and Monitoring Group believed the purpose of the trip was to procure military equipment, specifically spare parts for helicopters. It also noted that the two helicopter pilots did not apparently return to Eritrea and may have sought asylum in Europe.

The report underlined that the Monitoring Group received no replies to its official requests for cooperation on investigative and substantive matters from the Government throughout its current mandate, including to its formal requests for an official visit to Asmara. It has only been able to visit Eritrea twice in seven years, the last time in 2011! It did have two meetings with the Permanent Representative of Eritrea to the United Nations in New York, but largely had to engage with the government through individuals who have access to the country, including returning Diaspora Eritreans, academics, international journalists and diplomats. This was, it said, insufficient for the Group to carry out its mandate effectively.

In conclusion, the Monitoring Group suggested the UN Security Council should consider setting up a separate committee and monitoring group for Eritrea. It also recommended the Security Council request Member States consider offering the Government of Eritrea support to develop a program to strengthen the capacity of public financial management. The third suggestion, given the continuing military activities by Member States in and around Assab, is that Member States should be firmly advised about the need for compliance with the arms embargo on Eritrea.

It seems clear from the report that the Monitoring Group does not believe that the Government of Eritrea has been in full compliance with the sanctions regime during the last year, any more than it has over previous years. Eritrea remains consistent in its support for armed groups involved in cross-border activities and there is no evidence it has changed policies in this regard or in its approach to regional destabilization, even if the Monitoring Group found no firm evidence of specific support for Al-Shabaab. Eritrea has also remained determined not to allow the Monitoring Group access to Eritrea or access to any financial information. These are hardly the actions of a compliant state or one that it trying to respond positively to the UN Security Council resolutions or the sanctions regime.

…and a warning that Al-Shabaab is still a potent threat in Somalia

The UN Monitoring Group’s report on Somalia emphasizes that Al-Shabaab remains capable of launching large-scale attacks despite claims that the insurgency is weakening. This latest report was written before the electoral processes became fully operational over the last months and the Monitoring Group said its investigations had revealed “an incomplete, fragmented transition process with adverse implications for peace and security, security sector reform, arms embargo implementation, humanitarian and human right issues, conflict financing and natural resource governance, and corruption.”

Rather than agree with the current claims of continuing success against Al-Shabaab, still the most immediate threat to peace and security in Somalia, the Monitoring Group said it did not think the security situation had improved over the previous year. Al-Shabaab still had the ability to make large-scale attacks against AMISOM bases. It continued to launch attacks in Mogadishu, including at least six against hotels which had claimed a total of some 120 lives, including three parliamentarians and a Minister. Although Al-Shabaab had not launched a major terrorist attack outside Somalia since the massacre at Garissa University College in Kenya in April 2015, the Monitoring Group believed it still had the capacity and capability to carry out similar arracks, and it had, indeed, proclaimed its intent to attack the AMISOM troop-contributing countries. AMISOM is largely made up of troops from Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, Uganda and Burundi. The report also suggests that Al-Shabaab has “a robust and ideologically committed ‘middle management’ capable of easily stepping into positions vacated by assassinated senior leaders”, at least three of whom had been killed by drone strikes or other attacks in the last year.

The report emphasizes that the continuing problems of corruption, mismanagement and financial constraints have compromised the effectiveness of the Somali National Army. It says so-called “ghost soldiers” still remain on the payroll; and its investigation revealed significant inconsistencies in payment of salaries. It says the lack of regular salary increases has led to withdrawals from strategic positions and the subsequent temporary return of Al-Shabaab. The Monitoring Group also notes that its investigations have revealed probable misappropriation of rations and supplies arising out of a contract between the Federal Government and a private company. Support provided to the military by Member States may also have been subject to misappropriation. It provides details of these issues in the series of annexes attached to the report.

The Monitoring Group identifies a number of challenges in implementing the arms embargo, not least a failure of the Federal Government’s reporting obligations, and a lack of compliance by Member States supporting other Somali security sector institutions. The report says that the continued calls by the Federal Government for the complete lifting of the arms embargo are misleading. The embargo, the Monitoring Group stresses, is not an impediment to the import of arms and ammunition. Since the partial lifting of the arms embargo in March 2013, the Federal government has received more than 20,000 weapons and 13 million rounds of ammunition, for which Member States have provided advance notification. There has, however, been an increase in maritime stopping of illicit arms over the last year. The report also noted improvised explosive device attack on a Daallo Airlines flight from Mogadishu in February this year, which it suggests offers a substantial new threat to civil aviation in the region.

The Monitoring Group notes Al-Shabaab’s continued obstruction of humanitarian assistance and violations of international humanitarian law. This includes attacks on humanitarian workers and the diversion and misappropriation of humanitarian aid. Al-Shabaab has continued targeted assassinations of government officials, civil servants, parliamentarians, international agency staff, civil society activists and journalists. There has been an overall increase in the number of instances of the recruitment and use of child soldiers. Overall, armed conflict and insecurity led to the internal displacement of some 598,000 Somalis between 1 January 2015 and 30 June 2016.

The Monitoring Group does find some positive trends, one being the implementation of the ban on charcoal which has led to a declining volume of charcoal exports. However it also adds “there are currently no effective barriers to prevent Al-Shabaab from reverting to systematically taxing the production and transport of charcoal.” Al-Shabaab has also been offsetting the loss from charcoal by increased taxation of illicit sugar trade, agricultural production in southern Somalia and livestock. The Monitoring Group estimates that Al-Shabaab now gets up to $18 million a year in revenue from checkpoints demanding payment from trucks carrying sugar; it quotes a Somali intelligence estimate that $9.5 million is collected from taxing agricultural production.

It also finds that the Federal Government still lacks the capacity to regulate the financial sector and that Hawala companies do not have sufficient monitoring systems and due diligence procedures in place. The Federal Government is unable to implement targeted asset freezes imposed by the Security Council on individuals and entities in Somalia. Corruption, in fact, remains a serious problem, especially in regard to public contracts and misappropriation of public land for private gain.

In conclusion, the Monitoring Group stresses that sanctions have never been more relevant to assist the country through the process of conflict resolution and state formation. Al-Shabaab remains an imminent threat to peace and security; security sector reform remains far from complete; the obstruction of humanitarian assistance and violations of international humanitarian law remains of concern; conflict financing from natural resources is still a significant problem; and corruption remains a problem and the proposed regulations lack institutions to implement them.

The Monitoring Group therefore suggests a number of recommendations covering the tightening of the arms embargo, as well as dealing with the obstruction of humanitarian assistance and violations of international humanitarian law. It wants to see stronger action against violations of the ban on charcoal. With reference to threats to peace and security, it wants to see more cooperation over information sharing and a comprehensive, inclusive and affordable national security structure. It also wants a civilian-led auditing committee to report monthly to the Ministry of Finance and international donors providing security sector support; inclusion of efforts to deal with misappropriation in regional administrations and federal states; for the Federal Government to refrain from signing oil or development contracts until a model has been finalized with relevant Federal bodies, including a petroleum authority and a national oil company have been set up.

*****************